Europa

Template:Infobox Planet Europa (yoo-row'p-uh, Template:IPA2 Template:Audio; Greek Ευρώπη) is a moon of the planet Jupiter. It is the sixth nearest moon to Jupiter, and the fourth largest of Jupiter's moons. It was discovered in 1610 by Galileo Galilei (and independently by Simon Marius shortly thereafter) and is the smallest of the four Galilean moons named in Galileo's honor.

Etymology

Europa is named after Europa, daughter of Agenor, king of the Phoenician city of Tyre, now in Lebanon, and sister of Cadmus, founder of Thebes, Greece.

Although the name "Europa" was suggested by Simon Marius soon after the moon's discovery, the name fell out of favor for a considerable time (as did those of the other Galilean moons), and was not revived in common use until the mid-20th century.[1] In much of the earlier astronomical literature, it is simply referred to by its Roman numeral designation as Jupiter II or as the "second satellite of Jupiter". The discovery of Amalthea in 1892, closer than any of the other known moons of Jupiter, pushed Europa to third position. The Voyager probes discovered three more inner satellites in 1979, so Europa is now considered Jupiter's sixth satellite, though it is still sometimes referred to as Jupiter II. [1]

Orbital characteristics

Europa has a mean distance from Jupiter of 670,900 km (416,900 miles) and orbits the gas giant in just three and a half days. Its orbit is very nearly circular, with an eccentricity of only 0.009.[2]

Like all the Galilean satellites, Europa is tidally locked to Jupiter, with one hemisphere of the satellite constantly facing the planet. Europa is also being gravitationally pulled in different directions by Jupiter and by other satellites of the planet (tidal flexing). This gives the body a source of heat and energy, allowing the subsurface ocean to stay liquified, and driving subsurface geological processes.[3]

Physical characteristics

Internal structure

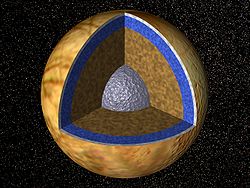

Europa is somewhat similar in bulk composition to the terrestrial planets, being primarily composed of silicate rock. It has an outer layer of water thought to be around 100 km thick (some, as frozen ice upper crust; some, as liquid ocean underneath the ice), and recent magnetic field data from the Galileo orbiter probe, which orbited Jupiter and studied Europa between 1995 and 2003, shows that Europa generates an induced magnetic field by interacting with Jupiter's field, which suggests the presence of a subsurface conductive layer which is likely a salty liquid-water ocean. Europa probably also contains a metallic iron core.[4]

Surface features

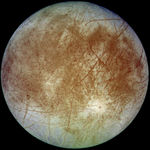

The Europan surface is relatively smooth; few features more than a few hundred meters high have been observed, but topographic relief in places approaches a kilometer (0.62 miles). Europa is the smoothest object in the solar system. The prominent markings crisscrossing the moon seem to be mainly albedo features, which emphasize low topography. There are very few craters on Europa, and its albedo is one of the highest of all moons. This would seem to indicate a young and active surface; based on estimates of the frequency of cometary bombardment that Europa probably endures, the surface is about 20 to 180 million years old [5] (the geological features of the surface clearly show a variety of ages).

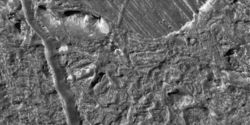

Europa's most striking surface feature is a series of dark streaks criss-crossing the entire globe. Close examination shows that the edges of Europa's crust on either side of the cracks have moved relative to each other. The larger bands are roughly 20 km (12 miles) across commonly with dark diffuse outer edges, regular striations, and a central band of lighter material. These may have been produced by a series of volcanic water eruptions or geysers as the Europan crust spread open to expose warmer layers beneath. The effect is similar to that seen in the Earth's oceanic ridges. These various fractures are thought to have been caused in large part by the tidal stresses exerted by Jupiter; Since Europa is tidally locked to Jupiter, and therefore always maintains the same orientation towards the planet, the stress patterns should form a distinctive and predictable pattern. However, only the youngest of Europa's fractures conform to the predicted pattern; other fractures appear to have occurred at increasingly different orientations the older they are. This can be explained if Europa's surface rotates slightly faster than its interior, an effect which is possible due to the subsurface ocean mechanically decoupling the moon's surface from its rocky mantle and to the effects of Jupiter's gravity tugging on the moon's outer ice crust. Comparisons of Voyager and Galileo spacecraft photos suggest that Europa's crust rotates no faster than once every 10,000 years relative to its interior.

Another type of feature present on Europa are circular and elliptical lenticulae, Latin for "freckles". Many are domes, some are pits and some are smooth dark spots. Others have a jumbled or rough texture. The dome tops look like pieces of the older plains around them, suggesting that the domes formed when the plains were pushed up from below. It is thought that these lenticulae were formed by diapirs of warm ice rising up through the colder ice of the outer crust, much like magma chambers in the Earth's crust. The smooth dark spots could be formed by meltwater released when the warm ice breaks the surface, and the rough, jumbled lenticulae (called regions of "chaos", for example the Conamara Chaos) appear to be formed from many small fragments of crust embedded in hummocky dark material, perhaps like icebergs in a frozen sea.

Subsurface ocean

It is thought that under the surface there is a layer of liquid water kept warm by tidally generated heat. The temperature on the surface of Europa averages about 110 K (-163 °C) at the equator and only 50 K (-223 °C) at the poles, and so the surface water ice is permanently frozen. The first hints of a subsurface ocean came from theoretical considerations of the tidal heating (a consequence of Europa's slightly eccentric orbit and orbital resonance with the other Galilean moons). Galileo imaging team members have analyzed Voyager and Galileo images of Europa to argue that Europa's geological features also demonstrate the existence of a subsurface ocean[6]. The most dramatic example is "chaos terrain," a common feature on Europa's surface that some interpret as a region where the subsurface ocean melted through the icy crust. This interpretation is extremely controversial. Most geologists who have studied Europa favor what is commonly called the "thick ice" model, in which the ocean has rarely, if ever, directly interacted with the surface[7]. The different models for the estimation of the ice shell thickness give values between a few kilometers and tens of kilometers. [8]

The best evidence for the so called "thick ice" model is a study of Europa's large craters. The largest craters are surrounded by concentric rings and appear to be filled with relatively flat, fresh ice; based on this and on the calculated amount of heat generated by Europan tides, it is predicted that the outer crust of solid ice is approximately 10-30 kilometers (5-20 miles) thick, which could mean that the liquid ocean underneath may be about 100 km (60-65 miles) deep[5].

The Galileo orbiter has also found that Europa has a weak magnetic field (about one quarter the strength of Ganymede's field and similar to Callisto's) which varies periodically as Europa passes through Jupiter's massive magnetic field. A likely explanation of this is that there is a large, subsurface ocean of liquid salt water.[4] Spectrographic evidence suggests that the dark reddish streaks and features on Europa's surface may be rich in salts such as magnesium sulfate, deposited by evaporating water that emerged from within. Sulfuric acid hydrate is another possible explanation for the contaminant observed spectroscopically. In either case, since these materials are colorless or white when pure, some other material must also be present to account for the reddish color. Sulfur compounds are suspected.

Atmosphere

In 1994, observations with the Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph of the Hubble Space Telescope revealed that Europa has a very tenuous atmosphere (1 micropascal surface pressure) composed of oxygen.[9] Of all the moons in the solar system only six others (Io, Callisto, Enceladus, Ganymede, Titan and Triton) are known to have atmospheres. Unlike the oxygen in Earth's atmosphere, Europa's is not of biological origin. It is most likely generated by ultraviolet sunlight and charged particles hitting Europa's icy surface, splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen. The hydrogen escapes Europa's gravity due to its low atomic mass, leaving the oxygen behind.

Possible life

It has been suggested that life may exist in this under-ice ocean, perhaps subsisting in an environment similar to Earth's deep-ocean hydrothermal vents or the Antarctic Lake Vostok. Life in such an ocean could possibly be similar to life on earth in the deep ocean. So far, there is no evidence that life exists on Europa but due to the likely presence of liquid water there are proposals to send a probe there (see exploration section).

Exploration of Europa

Most of our knowledge of Europa comes from the flybys by the Voyager and Galileo missions. Various proposals have been made for future missions. The plan for the extremely ambitious Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter was canceled in 2005.[10]

The 2006 NASA budget includes Congressional language imploring NASA to fund a mission that would orbit Europa. Such a mission would be able to confirm a subsurface ocean using gravity and altimetry measurements, elucidate the origin of surface features by imaging much of the surface at high resolution, constrain the chemistry of surface materials using spectroscopy, and probe for subsurface liquid water using ice-penetrating radar. The mission might even carry a small lander to determine the surface chemistry directly, and to measure seismic waves, from which the level of activity and ice thickness could be determined. However, at present it is far from certain that NASA will actually fund this mission, as funding for it is not included in NASA's 2007 budget plan. [11]

Another possible mission would use an impactor similar to the Deep Impact DI mission; it would make a controlled crash into the surface of Europa, generating a plume of debris which would then be collected by a small spacecraft flying through the plume. Without the need for an insertion and relaunch of the spacecraft(s) from an orbit around Jupiter or Europa, this would be one of the least expensive missions since the necessary amount of fuel would be decreased.[12]

More ambitious ideas have been put forward for a capable lander to test for evidence of life that might be frozen in the shallow subsurface, or even to directly explore the possible ocean beneath Europa's ice. One proposal calls for a large nuclear powered "Melt Probe" (cryobot) which would melt through the ice until it hit the ocean below. Once it reached the water, it would deploy an autonomous underwater vehicle (hydrobot), which would gather information and send it back to Earth. Both the cryobot and the hydrobot would have to undergo some form of extreme sterilization to prevent it from detecting earth organisms instead of native life and to prevent contamination of the subsurface ocean. This proposed mission has not yet reached a serious planning stage.[13]

A "Solar System Exploration Roadmap" published for NASA by the Universities Space Research Association in 2006 placed exploration of Europa high on its list, and suggested that plans for a "flagship-class" mission to Europa begin by 2008 with hopes to launch by 2015. [14]

See also

- Jupiter's moons in fiction

- List of craters on Europa

- List of lineae on Europa

- List of geological features on Europa

- List of Jupiter's moons

- Colonization of Europa

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Marazzini C. (2005) The names of the satellites of Jupiter: from Galileo to Simon Marius Lettere Italiana 57 (3): 391-407

- ↑ "Overview of Europa Facts" NASA webpage. URL accessed 15 April 2006

- ↑ "Tidal Heating"

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kivelson, M. G. et al, "Galileo Magnetometer Measurements: A Stronger Case for a Subsurface Ocean at Europa" Science 25 August 2000: Vol. 289. no. 5483, pp. 1340 - 1343. URL accessed 15 April 2006.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Schenk, P. M., Chapman, C. R., Zahnle, K., Moore, J. M. "Chapter 18: Ages and Interiors: the Cratering Record of the Galilean Satellites" In Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere. Cambridge University Press, 2004

- ↑ Greenberg, R. Europa: The Ocean Moon: Search for an Alien Biosphere. Springer Praxis Books, 2005.

- ↑ Greeley, R. et al. "Chapter 15: Geology of Europa" In Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere. Cambridge University Press, 2004

- ↑ Template:cite journal

- ↑ Hall, D. T. et al, "Detection of an oxygen atmosphere on Jupiter's moon Europa" (Abstract only) Nature 373, 677 - 679, 23 February 1995. URL accessed 15 April 2006.

- ↑ "NASA 2006 Budget Presented: Hubble, Nuclear Initiative Suffer" 7 February 2005 Space.com article. URL accessed 15 April 2006.

- ↑ Template:cite journal

- ↑ Template:cite journal

- ↑ Template:cite journal

- ↑ Template:cite web

External links

- Europa, a Continuing Story of Discovery at NASA/JPL

- The Calendars of Jupiter

- Are our nearest living neighbours on one of Jupiter's Moons?

Template:Moons of Jupiter

Template:Natural satellites of the Solar System (compact)

Template:Footer SolarSystem

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

als:Europa (Mond)

frp:Eropa (satèlite)

br:Europa (loarenn)

bg:Европа (спътник)

ca:Europa (satèl·lit)

cs:Europa (měsíc)

co:Europa (astrunumia)

da:Europa (måne)

de:Europa (Mond)

et:Europa

es:Europa (luna)

eo:Eŭropo (luno)

fr:Europe (lune)

gl:Europa (satélite)

ko:에우로파 (위성)

hr:Europa (mjesec)

it:Europa (astronomia)

he:אירופה (ירח)

la:Europa (satelles)

lv:Eiropa (pavadonis)

lt:Europa (palydovas)

hu:Europa (hold)

nl:Europa (maan)

ja:エウロパ (衛星)

no:Europa (måne)

nn:Jupitermånen Europa

pl:Europa (księżyc)

pt:Europa (satélite)

ro:Europa (satelit)

ru:Европа (спутник Юпитера)

simple:Europa (moon)

sk:Európa (mesiac)

sl:Evropa (luna)

sr:Европа (сателит)

fi:Europa (kuu)

sv:Europa (måne)

tr:Europa (uydu)

zh:木卫二

zh-classical:木衛二

| This natural satellite related article is a stub. You can help Orbiterwiki by expanding it.

|